The Athletic profiles Middlesex Magic

The secret sauce behind the Middlesex Magic, the underdog grassroots program that has produced multiple NBA players

KANSAS CITY, Mo. — It was around 2005 when the Middlesex Magic had built enough of a reputation that Reebok called coach Mike Crotty Sr. with a deal. The shoe company offered some gear and a few bucks for the Magic to become a Reebok team, and it was one of those arrangements that seemed pretty obvious to accept.

Crotty was on board until right before the first weekend of the grassroots season, when a rep from Reebok called and gave him the list of guys who would be on his team, a collection of players the company had placed in various prep schools in New England. The Magic were headquartered in Belmont, Mass., smack in the middle of Middlesex County, so geographically Crotty’s program was an ideal spot.

“You’re shitting me,” Crotty shot back. “The guys that are on the team are the people that I pick. What do you think this is?”

The deal was that Reebok would provide the funds, the gear and the players, and Crotty would coach.

“That relationship ended four weeks after it started,” says Bill Boyle, assistant director of the Magic, who cackles as he tells the story. “He told them to go stuff it. It was Classic Mike Sr. I loved it.”

Boyle played basketball at Marquette for Al McGuire and became a part of the Middlesex program after seeking them out when he was looking for a spot for his grandson to play grassroots basketball.

On a Sunday afternoon in Kansas City last month, he watched with pride as Mike Sr.’s son Mike Crotty Jr. coached the program to a clean sweep of the spring championships at both the 17-and-under and 16-and-under division on the Under Armour circuit in their first year as a shoe-sponsored program. He did it with his players, building the program into something that would have made his father proud. The reputation of grassroots basketball — known to most as simply “AAU basketball” — was long ago soured by arrangements like what Reebok was after years ago. Rosters were thrown together at the last minute with players jumping around from team to team every weekend. It has been (and can still be) like the current transfer portal version of college hoops on steroids. The product on the floor is sometimes disjointed and frankly hard to watch, especially when it turns into prospects chasing numbers — and, in their minds — scholarship offers.

But it’s not all bad. Sometimes you stumble into a program like the Magic, who play beautiful team basketball where the ball moves and they guard and they’re coached and they win. None of it, of course, is by accident.

The birth of this team was as innocent as it gets. Crotty Jr. was 11 and loved basketball and wanted to play as much as possible. So Crotty Sr. started the Magic. He coached two groups that first season, in 1993, an 11-and-under squad that his son played on and a group one year older. Crotty Sr. loved coaching. He’d grown up in Somerville, Mass., a working-class, financially-strained town where programs like the Middlesex Magic didn’t exist. As a young man, he didn’t have a lot of discipline in his life. He was a good basketball player, but college wasn’t really an option for him, and he wound up joining the Marines. After two years in the service, he settled in the Boston area with his wife, Theresa, and he got a job at Polaroid as a machine operator.

Coaching basketball on the weekends became his passion.

“He didn’t have great mentorship when he was young,” Crotty Jr. says. “I think he found the ability to offer to kids what he didn’t have — a coach, a leader, a mentor.”

The Magic, led by Crotty Jr. at point guard, turned into a pretty good team. His father’s goal was to give his son and his teammates the opportunity to use basketball to get an education. The mission worked. On Crotty’s Jr.’s team alone, they had eight players play college basketball. Crotty Jr. was the star of the bunch and ended up a two-time All-American and national champion at Division III Williams College. After playing professionally for a year in Germany, Crotty Jr. returned home, and his father’s program set him up for starting a life in basketball. Several sons of the Boston Celtics ownership group had played for the Magic, and after years of trying, Crotty Jr. talked himself into an internship. He parlayed that into a full-time job as director of player development, tasked with finding programs that would educate the players off the floor in areas such as the effects of alcohol on athletic performance. He basically served as a young mentor, even living with Gerald Green, whom the Celtics drafted 16th in 2005 straight out of high school. He was also one of the suits behind the bench every game, tracking stats that he says were relatively inane.

During his three seasons with the Celtics, they went from one of the worst teams in the NBA to winning a title in 2008. He got his ring and decided the nomadic lifestyle of the NBA wasn’t for him. He got a desk job and also started helping his dad coach the Magic. By that time, Crotty Sr. had expanded the program (12 teams from ages 11 to 17) and established it as a nonprofit.

Then in 2009, Pat Connaughton’s father, Len, reached out about Pat rejoining the program. Connaughton had played for the Magic in elementary school and had become best known as an MLB prospect. But he wanted to play Division I basketball, and the Connaughtons decided the Magic could make that happen. Connaughton played with the Magic the summer after his sophomore season. He immediately took a liking to Crotty Sr. “He held you accountable,” Connaughton says. “He was hard on me, but in the best possible way. I liked the way they did things. It was playing the right brand of basketball. It wasn’t necessarily your typical AAU team — run and gun, try to put together the best talented players and just roll the balls out and see what happens. It was structured practice. The ball moved. We ran sets. It was a brand of basketball that, regardless if I ever got to the Division I level or not, was going to teach me how to play basketball at the college level.”

Mike Crotty Jr. with Pat Connaughton after the Bucks’ 2021 NBA Finals win.

After his first summer with the Magic, Connaughton got some interest from the Ivy League but had just one Division II scholarship offer. With Crotty’s guidance, he put together a plan to get the high-major teams to take notice. He quit football and worked on his body in the fall. He lifted weights during the baseball season more so than he traditionally would. Crotty Sr. talked him through it all. On every game day during his junior season, they would talk on the phone. Then on the morning of Feb. 2, 2010, a game day for Connaughton, Crotty Sr. died suddenly. He’d gone to the hospital the night before, and doctors discovered an infection that infiltrated his blood. The source was unknown. He quickly became septic, and 16 hours after arriving, he died at the age of 57.

Crotty Sr. had already scheduled the program’s first tryout for third-grade players for Feb. 10. He’d been working clinics at local grade schools in an effort to expand the program’s reach. Friends told Crotty Jr. he didn’t have to keep the program running, but it turned out to be the best way to keep moving.

“We had our tryouts, and we put one foot in front of the other, and we kept going,” he says.

A few months later, his life and Connaughton’s changed forever.

The Magic went to AAU Nationals every year, a reason why Connaughton made the move to the program, and in the summer of 2010, this was his shot to gain attention.

It started with Crotty Jr. using a connection at Notre Dame to try to get the Irish to check out his star. His college teammate’s sister was married to Notre Dame assistant (now Delaware coach) Martin Ingelsby. Notre Dame sent assistant coach Rod Balanis to watch Connaughton at a tournament in Springfield, and Balanis messaged Crotty Jr. afterward that Connaughton was a “tough SOB.”

Crotty Jr. wrote back: “I appreciate that. I don’t really know what that means though coming from Notre Dame.”

“It means Mike (Brey) and I will be coming to see you guys in Florida.”

They were the first, but they’d soon have company in Orlando. Connaughton was like an indie band that blew up over a two-week stretch at the national tournament. Every game a few more coaches showed up. He’d put on a show from the moment he stepped in the gym, throwing down 360-degree dunks in warmups. Crotty Jr. made sure coaches could see Connaughton’s athleticism by drawing up alley-oop plays for him. He averaged 30 points and 20 rebounds. Word spread, and as more and more coaches started to show, Connaughton was unfazed.

“Every game I’d be like, I don’t think he can be better, and he was just better,” Crotty Jr. says. “It was incredible. He had it all going. Everyone was all eyes on him, and he was just spectacular. And really unselfish.”

The Magic ended up losing in the championship game, and Connaughton had nearly 40 high-major offers by the end of that summer. He eventually decided to go to Notre Dame.

“I don’t think I’d be in the NBA if it wasn’t for that week,” says Connaughton, now a sixth man for Milwaukee Bucks. “I know I wouldn’t have been at the Division I college basketball level if it wasn’t for that week. And if I wasn’t at the Division I college basketball level, I wouldn’t have had the chance to get better during those four years at Notre Dame that helped me have a chance to get drafted.”

The realization that he could help a player achieve his dream further motivated Crotty Jr. to grow what his father built. He split his time for three years between the Magic and his full-time job. Finally, one day his boss pulled him into the office and gave him the nudge he needed, and the assurance he could have his job back if necessary.

It hasn’t been. Today, the Magic have 59 teams. They have a girls program. Two years ago they signed a lease with the Boston Sports Institute to give them a home and allow Crotty Jr. and his assistant director (and cousin) Larry Hurley to run more clinics and camps. In the 2022 class, they have 25 players who will play college basketball next season. Two years ago in the class of 2020, they had 30 players make college teams. The 2023 class should top that.

The memory of Mike Crotty Sr. is alive with the Middlesex Magic, including the “MC” on each jersey.

On the grassroots circuit, 247Sports recruiting analyst Adam Finkelstein nicknamed them the sneaker killers, because Crotty Jr. estimates they won around 75 percent of their games against shoe company-sponsored teams over the last 10 years. “That’s maybe low,” he says.

Still, they remained unaffiliated; Crotty Jr. once discussed a possible arrangement with a brand and was asked who his next pro was. “I said, ‘I don’t know. If you mean NBA pro, it wouldn’t be our next; it would be our first, and I guess Pat Connaughton is our best chance because he’s a sophomore at Notre Dame and he’s pretty good,'” Crotty Jr. says.

The sneaker rep cut him off, telling him what they needed were pros.

“I was pretty turned off,” Crotty Jr. says.

Two years later, they had a pro in Connaughton. Three years later, they had another. Duncan Robinson joined the Magic after a so-so high school career where he didn’t play much until his senior season. He decided on a post-grad year and joined the Magic the summer before. Crotty helped put him on a path that took him to Williams College, which appeared in the national championship his freshman year and led to a chance to play at Michigan.

“He was one of the first coaches to really kind of believe in me and see me as somebody that can play in college,” Robinson says. “He really believed in me as somebody who can make shots. I remember if I’d miss, as the ball was in the air or clanking off the rim, he’d be screaming at me shoot again on my way back down the floor on defense. He was just always in my ear about just being aggressive and letting it fly.”

Robinson made it to the NBA as an undrafted free agent in 2018, and last August he signed the richest contract ever for an undrafted player with the Heat.

Around that same time, the Middlesex Magic finally found a match when Under Armour’s pitch was this: We want programs. We don’t want one-off teams with some high-major top 100 kid.

It was a sign of the evolution of grassroots basketball. It’s not perfect, but improving. Crotty Jr. was on board. And, oh by the way, he told them, he had one of those top 100 players too.

JP Estrella played last summer for the XL Thunder out of Maine. At the end of the summer season, he was only being recruited by Division II schools. His coach, Abi Davids, sat at the Estrella kitchen table last summer and asked the big man why he only had a Division II offer. “Because I’m a Division II player,” JP said.

“No,” Davids said. “It’s because I played you D2. You need to go D1.”

Davids believed the Middlesex Magic could give him the stage to get there. Estrella joined the program last fall, and twice a week the Estrellas make the four-hour round-trip drive to practice from their home in Scarborough, Maine.

The miles have paid off. On the first night at the event in Kansas City last month, Duke coach Jon Scheyer and Kansas assistant coach Norm Roberts sat in the corner of the court with eyes on Estrella. Syracuse coach Jim Boeheim was also there. Scheyer sent Estrella a text that night, and the scholarship offers have been pouring in.

“Oh my God,” Allie Estrella, JP’s mom who played at Boston College, says. “It’s crazy.”

Estrella now has a long list of high-major offers, and while he’s still unranked by the recruiting services, that’ll soon change.

That’s the power of playing on a shoe circuit. It speeds up the process of discovery.

Estrella had garnered that attention with a big first weekend on the UA circuit, helping the Magic jump out to a 4-0 start to the season, but his teammate Ryan Mela, a 6-6 slashing wing, was the star of the weekend for the Magic. Mela came into the weekend with just one D1 offer — Siena — and that somehow remains the case. (Attention coaches: You’re sleeping on that dude.)

The cool thing about what Crotty Jr. has built is his guys are simply trying to win games, get better and eventually coaches will take notice. One mid-major coach perked up recently when told about a few Magic players who were being under-recruited. “Those Middlesex Magic guys are the kind of kids who fit how we play,” he said.

Duncan Robinson, left, was the Magic’s second NBA player, but may not be its last.

The Magic players don’t seem to feel any kind of pressure with college coaches watching. The only time the U-17 team appeared anxious was in Sunday’s championship game.

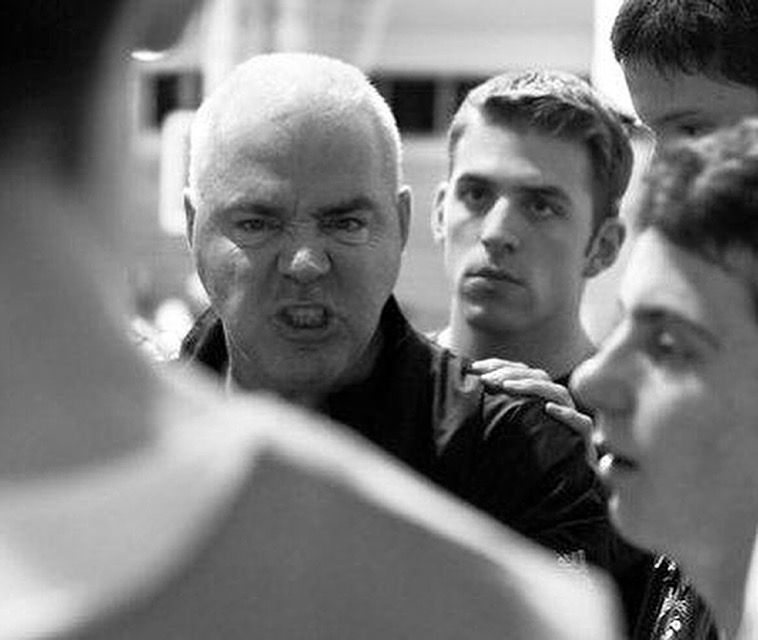

Crotty Jr. stayed composed on the sideline but delivered stern messages like a veteran college coach would.

“We can’t continue to make the same mistakes,” he said after another uncharacteristic turnover. “It’s not us.”

Mela, for the first time all weekend, struggled to finish at the rim. Midway through the second half, he came to the bench, and Crotty Jr. told him, “We need you. You’re gonna do it.”

Shortly after checking back in, he scored to cut WeR1’s lead to three. But the shots that had fallen all weekend still were not going in. Defense kept the Magic in it, as WeR1 tried to milk the shot clock every possession and shorten the game.

Crotty Jr. kept reiterating to his team that eventually the game was going to turn. With just under four minutes left and the WeR1 lead still at three, he declared during a timeout, “It’s our time. Let’s go.”

The Magic took the lead in the final minute, but two borderline calls went against them, sending the game to overtime. Crotty Jr. went to Estrella on the final possession of overtime, and he made what turned out to be the game-winning free throw with 9.2 seconds left on the clock.

The celebration afterward was a quick one for Crotty Jr. and his two assistants (Boyle and Magic alum Chris Giordano), because they had to coach the under-16 team in the championship immediately after. They won that too.

Connaughton, in the middle of the NBA playoffs, kept tabs on the results and talked to Crotty Jr. throughout the weekend. They’ve carried on the tradition he started with Crotty Sr. of talking every game day. He looks at the younger Crotty like a big brother, and he takes pride in where the program has come, a feeling that is mutual.

The championships in Kansas City were validation of what they’ve built, but Connaughton says what gives his friend real joy is seeing where his program takes his players.

He’s never forgotten his father’s mission.

“We’re out there trying to carry something out for a special guy that impacted so many of us that run the program now,” Crotty Jr. says. “And so, to me, waking up every day, my job is to help kids, coach basketball, and try to help further my dad’s legacy.”